Anonymous is now available as a DVD or Blu-Ray video disc and as streaming online video -- through Amazon.

This site can only urge once more... Please see it. In my experience, and that of many I've spoken to, it's so rich and densely packed that seeing it a second time is better than the first. (Review here.)

Anonymous also changes the conversation in the authorship debate in some fundamental ways. Its box office performance was good but not great: Falling somewhere between the revenues generated by Kenneth Branagh's 1996 adaptation of Hamlet and the 2004 Merchant of Venice (starring Al Pacino and Jeremy Irons). Nevertheless, it lives on and will continue to do so for many years to come -- albeit in less culturally conspicuous ways than in first-run cineplexes around the world, where it has been over the past six months.

At issue in this part of the interview with Orloff was a separate conversation I had had with the emeritus Berkeley English professor Alan H. Nelson about Anonymous. Nelson -- like most orthodox Shakespeare scholars and fans -- took great exception to actor Rafe Spall's over-the-top portrayal of Will Shakspere of Stratford as a bit of an illiterate oaf. (Pictured here, left to right, Sebastian Armesto [Ben Jonson], screenwriter John Orloff, Rafe Spall [Shakespeare])

Here is where the conversation picks up:

MARK ANDERSON: Let's talk about the portrayal of Will Shakspere of Stratford by Rafe Spall. How did you imagine him? How did that role evolve?

JOHN ORLOFF: Rafe is amazing. I love his performance in the movie. [The film] started off with the conceit that Shakespeare is a movie star. He's young. He's handsome. He's got an ego. He loves the ladies. He's ambitious. But in his heart, he really wants to act. That's what his art is, and that's what calls him.

He was always in our script as illiterate. The scene when Ben Jonson demands that he writes something in front of the Mermaid wits, that was always in the script.

MKA: But when you say illiterate...

JO: He couldn't write.

MKA: So in every draft, he was able to read his parts. But he just couldn't write.

JO: Correct. That was always in there.

And then Rafe came and read. And he really just broadened the character. He was always a little funny in our script. But Rafe broadened it -- but at the same time, I find his Shakespeare a little dark and menacing, as the movie progresses. And I like that about him. He's got a lot to lose, by the middle of the movie. And goddam it, he's going to protect it. There's a dark side to our Shakespeare.

I would ask [Spall] what he thinks about the [authorship] issue. I think Rafe was on our set a "closet Stratfordian." He would never really comment. Fair enough. But what he did say is, 'I think Shakespeare is the hero of this movie.' And I'd say, 'What do you mean?' And he said, 'If he didn't do this, none of it would have happened. Thank God he said Yes to Ben Jonson.' So we have these fabulous plays. That's how he thought of Shakespeare.

I started to think of Shakespeare as a Greek tragedy. He was the fool. He has the fool's role in our Shakespearean tragedy.

MKA: So Rafe thinks Shakespeare's the hero. You think he's the fool.

JO: In the sense that he's our comedic relief throughout the film, which I think it needs, because it's such a serious, somber and at times melodramatic story. It needs that lighter touch that Rafe peppers throughout the film.

And, listen, if you're going to go there. If you're going to say Shakespeare didn't make the plays, you don't want to make him a super-smart character, do you? Because you're kind of shooting yourself in the foot. You don't want to make an argument in the universe of the film that he's totally capable of making the plays. You want to make the argument of, 'No, he's some stupid actor.' You have that line when Oxford discovers that it's Shakespeare. The first thing out of his mouth is, 'An actor??!! An actor, for God's sake!' As if it's the worst thing imaginable.

It was also poking in the eye of professors -- my own professors. I would also argue that the thing scholars know least about is Shakespeare and his personality. And so I think the version we have of Shakespeare is just as justifiable as Joseph Fiennes' Shakespeare. The professor [Alan] Nelson might have a big issue with Shakespeare in my movie. But that's because he's coming to it with his own emotional baggage of his impression of who Shakespeare was. I'm not responsible for that emotional baggage. I can't help him with that.

MKA: When I spoke to Nelson about Spall's performance, you could feel the blood-pressure rise.

JO: I'm sorry. I don't mean to make people upset. At the same time, he's the one that's put him on this marble pedestal and made a big fat target on his forehead. Not I. I didn't put him there. I didn't make him this marble bust with no human emotions and longings. ... Well, they would say he has those things. But just skewed differently.

Listen, the first time you saw Amadeus. That laugh. It's pretty offensive if you're a big Mozart fan. He's an imbecile. It's hard to like Mozart, except for his saving grace. As a human being, he's a dick. The only thing that saves him is the fact that he has this genius. I sort of feel the same way about Shakespeare, minus the genius.

MKA: It's also true about Oxford.

JO: Yes, Oxford's an asshole. I tend to find most artists are, actually. By necessity, you are a self-absorbed, self-obsessed person if you're an artist. That is just who you are. I'm sure there are exceptions. But they are few and far between.

... I don't know a filmmaker or screenwriter who is not self-obsessed. And I don't mean that necessarily in a negative way. It can come off negative to your family, because you have no time for them. Or you have a bad temper because your head is really thinking about something else. And your child is asking you for a popsicle, and you're really trying to figure out the end of your third act. And so when you say, 'Not now' in a short, curt way, yeah. That's years of therapy for that child.

At the end of the day what you really are saying is, I know the world better than you do. I know it enough that I can share it with the rest of the world. And that is a very egotistical thing to say. And if you don't say that, you're not an artist.

It doesn't mean you're right. Just because you say it. It doesn't make your art right. But it is what makes you an artist. And that's a very difficult thing to come to grips with as a writer. There is a point where you go, Wow.

As a writer, I had nothing to say through most of my 20s. That's why I didn't write. And so there was a point when I thought, OK, I think I have something to say. That turned out to be Anonymous.

And ultimately, what I have tried to say, in vain, as though I'm yelling into a hurricane, is this movie is not about who wrote the Shakespeare plays? At all. That's the plot. It's about Is the pen mightier than the sword? Do words outlive and overwhelm might? That's what the movie's about. And that was worth saying.

MKA: Was The Soul of the Age [the title of the early drafts of the Anonymous screenplay] about the same thing?

JO: Not as much. The Soul of the Age was not as thematically driven. It had problems. That was one of the things that Roland came in and fixed. Or he pointed out the problem, and we fixed it together.

In retrospect, I was on that road. Trying to find it. Like any good collaboration, it required the collaboration [sic] of Roland to make it happen.

MKA: Let's talk about some of the other changes you made to Soul of the Age.

JO: There were no flashbacks in the original version. Or ... there was one flashback. The film originally was book-ended by Ben Jonson's arrest. And occasionally we'd pop back into [his story]. The original script also started around 1590, when Ben Jonson arrives in London. Now it's like 1596 or '97.

But the majority of the film took place in the 1590s. There were no flashbacks of Elizabeth and Oxford or Oxford's childhood. Any of that. That became a new element. Because in order to talk about the "Prince Tudor" theory, that has [the Earl of] Southampton as a possible bastard to Elizabeth, we decided it'd be more interesting to show that love affair. We wanted to see the bond between Elizabeth and Oxford.

What was in the main body of the film -- the present, 1600 -- Oxford and Elizabeth haven't spoken in decades. So how do you convey to the audience that there was a very deep love between the two of them, and that love produced a child?

You don't have to use flashbacks. But Roland and I thought it was doing double-duty. It was showing their love affair and how deep it was. But then also it was giving us a little bit of biography on Edward de Vere in a way to make us believe he could have written the plays. All his education, all of the relationships he had. And we thought we could take advantage of that.

And some of the events in his life are then mirrored in the plays. We made a very active choice not to do that too much. Which we could have.

That's a different movie. That's a different way to tell this story. To do a biography of Edward de Vere where every other scene you see a moment of Hamlet. You see a moment of this, you see a moment of that. That's not necessarily the movie that will get as many butts in chairs as the movie we made.

And then the whole third act became about something else. Originally, the stakes were: Is Ben Jonson going to tell the world that Oxford wrote the plays? Because at the end of act two of the old movie, Ben Jonson is so consumed by the injustice he's seeing. Both in his moronic friend becoming more famous than he. That just eats at him. And that de Vere is not getting proper credit. That also eats at him.

So in the original script, that is what drove the third act. Is Ben Jonson going to spout it out that Oxford is the real playwright? That was intercut with King Lear being performed and Oxford going mad from the plague a la King Lear. Running around in the storm. And then we used a lot more of his daughters in the body of the film, so the King Lear metaphor would pay off better. So that Bridget and Elizabeth and Susan had a bigger role to play in the film.

We also explored more of de Vere's ineptitude with money. We saw him getting poorer and poorer. Making bad investment after bad investment. The Northwest Passage. Sir Walter Raleigh was a character in that version. He was one of the characters that was our tool to get from the Mermaid's Tavern and to court. He was the guy who stepped in both worlds. He's not in our movie at all, obviously.

Now the third act is about the Essex Rebellion and who's going to be the next king. And so the stakes are totally different. And the thoughts are totally different. I like to say that everything that the Soul of the Age was is basically still in the movie. It's all just the B-plot. Jonson is still pissed at Shakespeare that Shakespeare is getting all the credit and is a moron. He's still sad that Oxford isn't getting the credit. And he still thinks about telling everybody that it's Oxford. And he goes to the Tower. And by going to the Tower, he's the one that destroys everything. He tells the Tower that Richard [III] is going to be played on Monday next.

MKA: Who's The Tower?

JO: It's our character we call Robert Pole, the captain of the guard. He still is considering opening up the truth. He goes to The Tower -- Pole, to the government, to Cecil, basically -- and says, hey. I want you to arrest William Shakespeare. He's going to play this seditious play as a hunchback next Monday. That's the information that warns Robert Cecil when the Essex rebellion is coming.

MKA: And then you have Marlowe's murder, which [historically inaccurately] Shakspere is strongly implicated in. Can you tell me more about that?

JO: So originally Marlowe was in the script. He was in Soul of the Age. The script took place a little bit earlier, when Marlowe was actually still alive. He was a slightly bigger character in that version. I think his death is unexplained in that version. Although maybe Shakespeare has something to do with it. I can't remember. But when we did the version that is now Anonymous, we knew that push[ing] up the dates to closer to 1600 rather than 1590, we knew that Marlowe was actually dead. We probably wrote 20 drafts with Roland. Some of them smaller changes, some of them with major changes. But some of those drafts had Marlowe not being in the movie at all. Because we knew the problem with the fact that he was killed in 1593. And our movie takes place past that.

But then when he was not in the script, we felt his absence. Because how can you have a movie about the Shakespeare authorship issue and not have Marlowe in it? Otherwise it's this lingering question. Like, 'Wait a minute, I heard something about Marlowe being the real author.'

MKA: But you didn't have [Francis] Bacon...

JO: We never had Bacon. I've never been a Baconian. I guess you're splitting hairs if you're a Stratfordian -- what's crazy. But the Baconian theory always seemed crazy to me. As does the Marlovian one too. I guess I never found Bacon an interesting character. But Marlowe's a really interesting man. It was, again, just a dramatic choice. We had to have him.

Then there was the choice of, OK, he's got to die. If something that important happens in the script, it better be related to the rest of the movie. You just can't have, 'Oh and by the way he was found dead the other day.' That means one of our other characters has to be implicated in that death.

So of course who are you going to set your sights on? William Shakespeare.

MKA: I have to plump for my own version, because I've read some great Oxfordian work on this. Because Marlowe was a secret agent. And I think, arguably, Marlowe knew about Robert Cecil's dealings with King James about the succession. And that's treason. So that's why he was murdered. ... But I take your meaning that you can't just introduce someone to the audience and just have them turn up dead in a bar.

JO: You can't do that in a movie. You just can't. So I'm taking my knocks when people say, 'Marlowe was dead when your movie takes place!' I go, Yeah. And the Bridge Over the River Kwai was never blown up. What's your point? This is a movie. Salieri didn't kill Mozart. There weren't two little sweet boys helping Lawrence of Arabia across the desert.

MKA: So you wanted to defend other choices you made in this film?

JO: The big ones are Marlowe, Richard II. [n.b. Orloff discusses the movie's conflation of Richard II and Richard III in the previous portion of the present interview.] I've noticed a couple reviews have gotten very [upset] about the fact that we show one or two performances in The Rose with torches at night. And they are quite correct. The Globe and The Rose didn't show plays at night, because candles were so expensive. And it was dark, and nobody wanted to walk home in the dark. They are absolutely right. But it's a film. And we didn't want to show the same old shot over and over every time we cut to theater. That's called drama.

To say we didn't know what we were doing because we made that kind of error really denigrates the amount of research that hundreds of people did for this movie -- including the [director of photography], who very well knew that she was breaking a rule. But she thought we had to spice it up.

I was very fortunate to be on set for the whole movie. That's a real rarity in the film business. But Roland really likes having the writer on set. And it was a good thing I was there, too, because we did a lot of rewriting on set.

MKA: How long was the shoot?

JO: About three months. Ten weeks, eleven weeks. But a month or two of prep ahead of that. So we all arrived in January of 2009 and left in June -- from Babelsburg.

But we had this enormous building that was like our office building. Each little office you'd go to another department head. And the degree of care that every department took to get it right ... I'm instantly reminded of the special effects people who did their damndest to look at maps. And when they were recreating in the computer London in 1600. They really tried to get it down to the street level. Where was St. Paul's. And where was this... and you can see St. Paul's from this angle. This was not making shit up. This was trying to get it to look more right than it's ever looked in a movie before.

And here's another interesting thing that I loved. Our wardrobe stylist, who was amazing. It was a low-budget movie, believe it or not. These are the kinds of things you just don't notice. But she thought -- and if you watch the movie, you will notice -- the older Elizabeth gets, the more baroque her dresses become. She starts out as a young woman, and she's wearing a very plain, blue satin dress. And her hair's long and down. And each subsequent time period you see her in, her dresses and her hair become more and more elaborate. Till at the end, in the final scene, when Vanessa [Redgrave] is saying you can have Southampton, to de Vere. We call it the Michelin Man outfit. She's wearing this enormous white thing with giant poofs. And this huge hair-crown... this elaborate thing.

Another example is the plays within the play. We got this unbelievably brilliant theater director named Tamara Harvey, who's a protege of Mark Rylance. We asked for some Shakespearean directors to join our movie, and they all said no. Tamara, who is a Stratfordian, said yes. She came up with this really interesting idea as well -- which I didn't realize until she told me. Similarly each staging of a Shakespeare play within the movie gets simpler and simpler and simpler. Until at the end, it's Hamlet, and it's just a man wearing black, talking to the audience.

But it starts with Henry V. And all that craziness and drama and cannons and elaborate stagecraft. And you'll see Romeo, which is also very elaborate. And then Macbeth -- and it gets simpler and simpler. Each subsequent play you see, until it's just about the words. It's just about a man on a stage using words. Very clever, and very well thought out.

And all the departments did that. The props, everybody. So I'm very proud of that stuff.

MKA: At the New Yorker Festival screening, I met the guy who did all the calligraphy in the movie. Roland joked that 'This is the man who really wrote Shakespeare.'

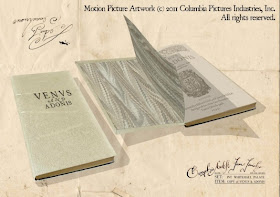

JO: Oh, yes Jan [Jericho]! His office was just filled with stuff. I begged him, and he gave me a copy of our Venus and Adonis. The little book. We had four of them made. And he hand-bound them himself. The Venus and Adonis that's getting passed around, and I got one of them.

MKA: Shame on you! That was 1593!

JO: I know, I know. There's another great example that we hemmed and hawed a lot about. But I would argue the same thing you argued about Marlowe. Namely, one can make the argument -- and I would -- that Venus and Adonis is about the succession issue. And certainly in the context of our movie, it's a young lover reminding an older lover of that love. And literally, saying, your duty is to breed.

MKA: Certainly that's the first 17 Sonnets too.

JO: We talked about using The Sonnets instead of Venus and Adonis. We did have that conversation. And I'll be honest with you: It was the sex in Venus that I wanted. Because [part of it is] about oral sex. It's pretty graphic. In a good way. And that's passionate. The Sonnets aren't quite as passionate. Drama trumps reality. I could have used The Sonnets, which were published in [16]09. But who knows when they were written. So we could have done The Sonnets and had more of a veil of, well, who knows when The Sonnets were written. But we made the very conscious choice that Venus and Adonis just fits our film better. The younger lover with the older woman. It's incredibly sexual. And he literally says, Your job is to have children.

But I would argue that Venus and Adonis was about that anyway. If you are an Oxfordian, it is still a message to the queen saying, You need an heir. Whether it happens in 1593 or 1600 or 1601 is irrelevant. Emotionally, I say it's still an Oxfordian truth. Even though, yes, we shifted it a little bit.

But I would also counter, let's not talk about the dating of anything. Don't tell me about shifting dates, Mr. Stratfordian. Dates are a very convenient thing in Shakespearean scholarship.

To us, it was about what Shakespeare said, not when he said it.

MKA: What about the cast? How much push-back did you get?

JO: Absolutely none. I hear that it was one of the hot scripts that everybody wanted to work on in Britain, when we started to cast it.

MKA: And you wanted specifically British actors, right?

JO: Only. Roland tried to make the film five years ago, right after The Day After Tomorrow. And we were actually starting to cast it. We were in pre-production. We were hiring crew. We were hiring the cast. It was the first time he started to talk to Vanessa Redgrave about it. And we were talking to other people, who didn't end up being in the movie. So we won't talk about them. And we had a lot of pressure from the movie studio to hire American actors that would be box office draw. And at a certain point, Roland said, that's not the movie I want to make. And he walked away.

MKA: Was it specifically because he wanted a British cast?

JO: Yes. That was a big part of it. It wasn't the only thing. Things are more complicated. The budget was going up. At a certain point, he said, You know what? This is not feeling right. So when we tried to make it again, he was really clear that he wanted to cast whoever he wanted. And the studio said, Great. Fine. Go with it. Just as long as you make it for a price. You make the movie under a certain number.

And so we started going out to these young, up-and-coming actors. And it was about who's best for the role, actually. As opposed to who would sell more popcorn. Which you don't get to do very often anymore. And I've got to tell you, I constantly pinched myself, almost every day. Seeing these actors. I think, top to bottom, this was a pretty amazing group.

MKA: It's an incredible ensemble piece.

JO: It's written as an ensemble piece. All the actors loved it. Even actors that don't appear in the movie that much, they have a ton to do. Ed Hogg, who plays Robert Cecil. He's not in the movie that much, actually. But he's fantastic. And he has an arc. He starts off as that jealous little kid -- obviously not played by Ed. And then he has this arc in the movie. Which second or tertiary characters don't always have in a movie.

Shakespeare, the same thing. Jonson, the same thing. Elizabeth, the same thing. They all have these really interesting problems and goals. And all of them intersect and intermesh and conflict. And that led to a really great ensemble piece. With really great actors. I mean, David Thewlis. He had to play his character [William Cecil] at five different ages.

MKA: There were some really great performances. But him in particular, I thought, he should be nominated for Best Supporting Actor.

JO: He's really great. Really great. Let me just tell a little story for me -- which was when it started to go around in Britain, they all thought it was written by a Brit. The script. So I got my British "-isms" down, because I fooled the Brits. And it turns out that Vanessa has wanted to play Queen Elizabeth her whole life. She's obsessed with Queen Elizabeth and Tudor times. And she's an unbelievably smart human being. So the first time we sat down, I was rather intimidated. She's also the most gorgeous 72 year old I've ever laid eyes on. And we sat down, and she starts challenging me, basically on every line Elizabeth says. 'I don't think Elizabeth would say that.' And you know what, sometimes she was right. When we talked it through, she was right. And other times I would say, You know what, Vanessa, we need Elizabeth to say that for the plot. And she would say, OK. Got it. Let's move on. She was unbelievably wonderful. She really had some great points.

And the entire scene when Robert Cecil gives her the Act of Succession, with James's name on it, that she throws away. That entire scene was Vanessa's idea. It wasn't in the draft. She was really, as an actor, interested in the idea that Elizabeth in her last days of her life sat on a pillow, sucking her thumb. Because her teeth were all gone. And that image was stuck in Vanessa's head. She really wanted to do it. We figured out a way to make it happen and insert that plot point in the scene. And that was all Vanessa's idea. As were the blackened teeth. And trust me, she knows way more about Elizabeth Tudor than I did.

MKA: You read accounts of Elizabeth's final days when she was sucking on what they called a "sweet bag," because her breath stank so bad.

JO: And when Essex comes into her boudoir, she's not wearing a wig. It's very brave for an actor to do. Actors often will say, No, I don't want to do that. And you're kind of stuck. But Vanessa was totally brave to appear unattractive. Trust me: Most actresses don't [want to do that]. She was unbelievably great to work with.

MKA: Tell me about working with Vanessa and her daughter [Joely Richardson, who plays young Princess and Queen Elizabeth].

JO: It was interesting, because they had very little overlap. They weren't working on the same days. They were playing the same characters. It was kind of a coup. We were hoping for it. And Roland had made a movie with Joely before. She's in The Patriot. She'd already known Roland and known what a lovely man he is to be with and make movies with. So it didn't take too much arm-twisting to get Joely to do it as well. But Vanessa was always our first choice. Especially because I'd written Elizabeth, even more so in the script maybe than in the movie, as somebody who's befuddled and confused. And may have something akin to Alzheimer's. Or she's smarter than any of them and is just pretending.

MKA: I don't see how that second option would play out.

JO: At the very end when she talks about why she didn't dump the Cecils. I thought that was an extreme moment of lucidity. And she hasn't seemed so lucid up to that point. It's something that's more in the script than in the film. Her doddering and possibly faking it.

It's an interesting situation, when you think about it. Because she's old, and she knows she's old. And she's dying. But she must have some sense of not having quite the control over her court that she did in her prime.

MKA: Although she loved up until her dying days for people to flatter her about her beauty, and pretend that she's young again...

JO: Of course. But that's not controlling the court, is it? That's not actually being in control. And I thought that was an interesting dynamic to play. Is she sensing that things are being done without her knowledge? And what do you do with that? I thought it would be interesting thing to play off this idea of her response to it is to withdraw even more. And to observe and only make choices when she absolutely has to.

MKA: What about Rhys Ifans [as Edward de Vere]?

JO: Rhys was great. Rhys was a surprise. In a lot of ways. The first surprise was that he wanted to play Oxford. He's always the silly... he's the Shakespeare character often.

MKA: Roland said Rhys was initially considered for that role, right?

JO: Yes. But he's a little old for that role. So that was never going to be an easy fit. But it was possible. And Rhys really wanted to play Oxford. And I remember seeing the tape of him -- an audition tape. He read for it. He just became possessed. On set, it was amazing.

MKA: Is he a method actor?

JO: He's not. But he's all but. He would come on set, and he'd be in his costume. And he would be a different human being. Rhys is rock and roll. He'd like to be Mick Jagger. He dresses like that. He walks like that. His movements are kind of like Mick Jagger. He does the thing with the wrist when he's walking. But, man, you put him in the de Vere outfit. And he sat in a director's chair. And you knew: Don't come fucking near him. He's in his zone. He's becoming de Vere. I actually think his performance is extraordinary. The depth. One of the negatives of having such an ensemble piece is you don't spend a lot of time with any one character. And Rhys is in the movie probably a lot less than you think he is. But the force of his personality and the character he's created is so strong, it feels like it's his movie. I think that's a testament to his acting.

MKA: Do you think if, by Academy standards, his total amount of screen time would only add up to a supporting role?

JO: I don't know.

MKA: But you're right. He's hovering. There's a presence that's not onscreen. His character is so...

JO: Über.

MKA: Yeah. To me there's a lot even just in his glances. It's just a little bit. It's not the sort of thing that would get a lot of buzz or media attention. Oscars are always about "Most."

JO: Well he gets close to chewing the scenery. Not in a bad way. That's the movie. The movie's a big melodrama. It is a little bit bigger than life. It is a Greek tragedy. And Rhys played the character big. I think greatly. It's not a natural, Stella Adler sort of performance. It's not naturalism. But it feels very real.

We thought of Oxford as a very arrogant guy, and his self-appearance was incredibly important to him. Which we know historically. Those little things help actors. You give a little thing like, Well, this guy was a clothes-horse. An actor will suddenly start doing stuff with this... Now that he knows he's a clothes-horse, he uses that. And it becomes part of the character.

He's a fucking earl, and he's going to be arrogant. He's going to be that. 'Voice? You have no voice. That's why I chose you.'

MKA: Of course that line is invested with so much irony, because who's the one without any voice?

JO: Of course. Exactly. It's de Vere. And Ben Jonson ends up becoming the first Poet Laureate of England. He had quite a voice, in the end, Ben Jonson. And I would say probably in his lifetime was way more famous than Shakespeare ever was.

MKA: So how do you want to see this movie propagated out into the world?

JO: It's meant to be a fun movie. This is not a history lesson. We strove to not be that. We're not trying to prove Oxford wrote the plays. That is a different movie. What I hope people get out of it is A) A really fun time. B) A deeper appreciation of the process of writing. And C) I hope it makes people go on the Internet and just start to research the authorship issue.

I don't have a problem with people saying Shakespeare wrote the plays. I think it's a perfectly justifiable conclusion to come to. I think it's open to debate. I think there's reasonable doubt. And I happen to come down on a different end of that question. But I think it's incredibly reasonable for people to come to that conclusion. And if they've done a little bit of research, they've learned a little more about Elizabethan England. And they've learned a little bit more about Shakespeare's plays -- because you need to do that to understand the research -- then that's all good.

At the end of the day, we're talking about Shakespeare, and we're talking about art, and we're talking about the intersection of life and art. And however you come out at the end of the day, I'm fine with it.

MKA: Do you see Anonymous as something that launches a new generation of the authorship debate?

JO: I hope that would happen. I think it's inevitable that it will bring attention to the authorship question. The thing that has stuck with me: Charlton Ogburn, at the end of that Frontline episode, talking about de Vere and how he's unknown to history. It gets very emotional at the end.

MKA: Ogburn quotes "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow," and he actually starts crying.

JO: I think that this movie will at least put Charlton Ogburn's fear to rest. People will now know the story of Edward de Vere, and the conversation will happen. And that's what Stratfordians are afraid the most of.

It's not that they're afraid that Shakespeare isn't going to come out ahead. What they're afraid of is the understanding that they are actually no more experts than anybody else on Shakespeare. That's what I think they're most afraid of. What they've been teaching for 200 years in critical studies is all really just their interpretation. With scant evidence.

That's the thing that scares them the most. They are unneeded in this process.

At what point do you go, 'Well you don't really need another biography of William Shakespeare, because you made up the last one.' And the one before that and the one before that and the one before that.

MKA: At the New Yorker festival screening of Anonymous, [Shakespeare professor] James Shapiro publicly took on Anonymous and went there -- he said this was a movie of blonde-haired people who were concerned with their bloodlines.

JO: When you wrote it, I thought, He's got to be exaggerating. It must have been more oblique. And then I read it from a third-person [account]. And they said the exact same thing. And I said, Holy... What?? This is where we're devolving to? It's Nazi propaganda?? That's how much you hate it? Wow! That's going far.

But I've had my own little issue with Shapiro. We had our own little exchange in the press. In the last year. Because I was quite upset with his mischaracterization of the [1987] Moot Court. Where he wrote this op-ed about us. How dare we write this movie. And he said, 'Well. Three U.S. Supreme Court justices unanimously voted for Shakespeare as the author.'

And, technically, to the letter of the law, [that's true.] But that would not be an accurate representation of their actual opinions of who wrote the plays. And to say what he said is intellectual dishonesty.

That's the thing that upsets me the most. You know what, there is a good case that Shakespeare wrote the plays. But don't mischaracterize your point. Your case is not locked, sealed and delivered. And that's the problem.

But don't make stuff up to fill that gap. That's the thing that upsets me the most about this whole thing is the intellectual dishonesty. Which dovetails into this idea of -- well, if we're so crazy, and we're so wrong, and you're so sure... why don't you want to talk about it? One would think it would be rather easy to disprove everything we say if it's so perfect -- your argument. To me, the oddest moment is when I asked Professor Nelson in our conversation, Did he think there was a problem at all?

When he said, 'No.' That's the thing that upsets me the most. Because there is a problem. To deny there is a problem is dishonest. The problem might end up being solved one day in Shakespeare's favor. Or it might not. But I really think there's a problem.

MKA: And Anonymous poses the question -- and introduces the question to more people than anything before it.

JO: The power of cinema is amazing. The depth of its reach. Which is one of the reasons why the Stratfordians are afraid. Because rightly or wrongly, they are correct in assuming that people will think everything they just saw is real. People do. They watch Amadeus, and they think that's what really happened. You and I really know it wasn't. But a lot of people don't take the time to find out what is real and what isn't. And these movies live way longer than books do. They're much more immediate than books. And this will be on DVD, and it'll be streaming. I bet you Shakespeare classes will show it. Some will.

Just like I watched Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet in seventh grade. They show bits of Band of Brothers in high school history classes. Somewhere, somehow, young minds are going to see this movie.

It was interesting at the college [screenings] that we went to. The audiences were almost 99 per cent students. And these young people who had never heard of the Oxfordian issue tell me how they were sobbing at the end of the movie. They're going to go find out what was true and what wasn't. So that's going to change things. The truth will come out.

Venus and Adonis book cover design (c) 2011 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc./JanJericho.com; photographs courtesy of John Orloff.

Bravo, Mark. Bravo, John. This is a remarkable piece of work.

ReplyDeleteExtremely informative interview. Just one thought about the hypothesis that Shaksper of Stratford was an illiterate actor. Let's not forget that there's no documentation that "Shakespeare" acted after 1604, the year of de Vere's death. An alternate narrative is that insiders referred to de Vere as "Shakespeare" when he acted at court. It's difficult to imagine the illiterate Shaksper being able to memorize his lines.

ReplyDeleteSome Stratfordians dismiss the Oxfordian narrative by insisting, "The plays were clearly written by an actor who knew theater well." We need to meet that reasoning head on.

'It's difficult to imagine the illiterate Shaksper being able to memorize his lines.'

ReplyDeleteTrue - but remember that many people who are unable or barely able to write are still able to read. This may well have been the case with Shakspere.

Great interview btw, thanks for that.